Donald Wayne Viney

“Events far reaching enough to people all space, whose end is nonetheless tolled when one man dies, may cause us wonder. But something, or an infinite number of things, dies in every death, unless the universe is possessed of a memory, as the theosophists have supposed” (Borges, 39).

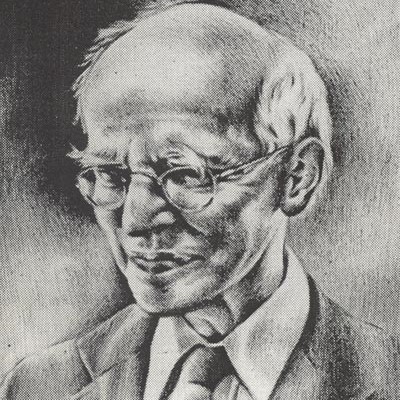

I knew Charles Hartshorne for the last two decades of his life. One does not easily forget a meeting with him: the smiling eyes behind wire-rimmed glasses; the disheveled eyebrows; the beak-like nose; the voice, pitched high with age, cracking with excitement at some philosophical insight; the contagious sense of self-importance tempered with humility before the genius of Plato, Peirce, or Whitehead (or a musician); the witty anecdotes; the fondness for birds; the blink and nod that bade a charming farewell. His small frame and his mail order clothes only served to bring into disarming relief that one was conversing with a surviving member of the pantheon of twentieth century philosophers.

Never content to philosophize ahistorically, Hartshorne self-consciously wove threads from the masters of the past into the tapestry of his own neoclassical metaphysics, often discovering in the process unfamiliar insights of great thinkers and great insights of unfamiliar thinkers. He once told me that he sometimes practiced philosophy by imagining himself conversing with the giants of the past. Reading Hartshorne, one is able to participate vicariously in that lively conversation. That he found no dichotomy between philosophy and its history is a credit to his genius. That he articulated a vision of things that, despite its shortcomings (of which he was aware), is often rigorous enough to meet the demands of reason and rich enough to satisfy our emotional nature qualifies him as one of the great metaphysicians—perhaps the greatest—of his century. My favorite description of Hartshorne is from John B. Cobb, Jr., who called him “A strange and alien greatness” (Cobb 1992, 84).

Thanks to Donald Crosby, I first saw Hartshorne in Denver, Colorado in April 1976 while I was still an undergraduate.1 My memories of that conference are not as clear as I would like. The conference was relatively small with chairs arranged in an unusual manner, in a circle, and a lectern on the circumference from which Hartshorne spoke. There were several philosophers of Asian descent and I remember one fellow whose remarks on Hartshorne’s paper went on too long and he kept referring to Hartshorne as “Professor Hot-so.” Also in attendance was John Wisdom (1904-1993), who was at the time a visiting professor at Colorado State University. Crosby told me that he asked Wisdom what he thought of Hartshorne’s talk. Wisdom simply replied, “I could make nothing of it.” Coming from one of the leading proponents of ordinary language philosophy, this could have been considered a serious philosophical claim. I was not sophisticated enough philosophically to make much of Wisdom’s comment, or of Hartshorne’s talk. Only much later would I learn that Hartshorne had many years earlier criticized Wisdom’s famous article “Gods” (Hartshorne 1962, chapter 5).

In one of Crosby’s classes, I had come across Hartshorne’s name while researching a paper on the ontological argument for God’s existence. His ideas made no lasting impression on me at that time, but then I had only the vaguest notion of what he was saying. I did not meet Hartshorne or recognize his genius until November 1979 at a philosophy conference in Austin, Texas. In one of the plenary sessions, Alvin Plantinga presented a paper on the ontological argument. Hartshorne was in the room not far from where I was sitting. In the question and answer session, a man in the back of the room stood up and, with a slightly patronizing air, said: “Your view requires that existence is a property. But it must be a rather strange property. Like Russell said, if you ask a child to describe a zebra, the kid would say that it has black and white stripes and that it looks like a horse, but not that the zebra exists.” Plantinga deflated the swagger with a flick of his wit: “The child also would not say that the zebra is over two inches tall, yet that is indeed a property of the zebra.” It was obvious to me that one does not challenge Plantinga with half-baked objections. Hartshorne then rose to address Plantinga. It is one of the small regrets of my professional life that I do not remember the details of that exchange. Perhaps I was simply not sophisticated enough to follow the argument; after all, I hadn’t yet digested much modal logic. What I recall, however, is that Plantinga and Hartshorne disagreed on some point but the intellectual match was a draw. Plantinga showed great deference to the older philosopher; there would be no witty rebuttal. Hartshorne seemed satisfied to agree to disagree.

I did not go to the Austin conference expecting it to redirect my philosophical career. But that is what happened after I met Hartshorne. The encounter perfectly exemplifies both Hartshorne’s belief in the reality of chance as well as his gregarious personality. I was a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma in Norman but I was in Austin to attend the conference with a fellow graduate student, Peter Hutcheson (who would spend his career at Texas State University). At lunchtime Peter and I searched for a place to eat other than the school cafeteria. After an exasperating hour of hunting for a place to park the car we returned to the convention center—to the cafeteria. We happened to sit at a table adjacent to where Hartshorne was eating. When the people at his table left, Hartshorne asked if he might finish his meal with us. For the next half-hour he entertained us with philosophical remarks and humorous anecdotes.

As a result of that serendipitous luncheon, I began a serious study of Hartshorne’s writings. Hartshorne convinced me, among other things, that there are two ontological arguments suggested in Anselm’s Proslogion and that the second escapes the standard criticisms of the first. I determined to write my dissertation on some aspect of this question. Unbeknownst to me, the chair of the philosophy department, Robert Shahan, sent my prospectus to Hartshorne and invited him to serve on my committee. Hartshorne accepted the invitation but suggested that I write on his cumulative or “global” argument for God’s existence, of which the ontological argument is one strand. The result was my first book, Charles Hartshorne and the Existence of God (SUNY Press 1985).

My acquaintance with Hartshorne really began in February 1981 when he visited the campus in Norman to present a paper and to discuss my project. For four days I chauffeured him around the Norman and Oklahoma City areas in my light blue 1973 Volkswagen Beetle. The incongruity of a fledgling graduate assistant having the undivided attention of a world famous philosopher did not escape me. There was also the contrast of the mundane and the profound. I took him to a drug store to buy ointment for a bug bite and we discussed the great questions of metaphysics. Hartshorne was self-confident and understood his importance to philosophy, but I never found him to be egotistical. He remarked that his goal was to write the best philosophy of any octogenarian. When I mentioned Whitehead—who lived into his eighties—he clarified that he was not trying to be greater than Whitehead.

Hartshorne was convinced that honest inquiry in philosophy would lead to truth, notwithstanding philosophy’s apparently intractable problems and its seemingly interminable debates. His wide-ranging knowledge and imaginative arguments lent an air of authority to his pronouncements. At the First Unitarian Church in Oklahoma City he gave a sermon in defense of freedom and its implications for theology. Afterwards a man asked him, “Mortimer Adler [in How to Think About God (1980)] speaks of God as the uncaused caused. How does this relate to your own views?” Hartshorne replied, “The idea of an uncaused cause is a perfect example of a half-truth parading as the whole truth. A God who loves and is loved by the creatures is anything but unmoved. It is true that God’s existence is uncaused, but this does not mean God is in all respects uncaused.”

Fritz Rothschild described the God of Abraham Heschel as “the most moved mover” (Heschel 1959, 24). Hartshorne, who greatly admired Heschel, amended this to “God is the most and best moved mover” (1991, 69-70). Hartshorne’s defense of the idea that God is in some respects related to, or moved by, the creatures is one of his signal contributions to philosophical theology. I showed Hartshorne a newspaper article in which his book The Divine Relativity was mislabeled “The Divine Reality” (Anon 1981). Pointing to the error he remarked, “There is only one mistake in this article. Any number of authors have talked about the divine reality. How many have seriously considered the divine relativity?” The implication was that very few had seriously considered the divine relativity, and he was right about that. After Hartshorne, however, it is not possible to have a critically informed discussion about theology that has as its default position that God is in all respects unchanging or unmoved.

There may be no one in the twentieth century who more nearly approximated what Spinoza called the intellectual love of God than did Hartshorne. Not everyone was happy with his willingness to talk about the divine with such confidence. When my book appeared, a friend of my father, Prescott Johnson, wrote to congratulate me, but added, “I have trouble with Hartshorne’s literalism; I really don’t think that he knows as much about God as he thinks he does. But I enjoy reading him and have enjoyed the few times that I’ve talked with him.”2 Martin Gardner, one of Hartshorne’s former pupils, echoed this sentiment, “Hartshorne’s writings are stimulating to read and seldom opaque, but I am always made uncomfortable by the fact that he seems to know so much more about God than I do” (Gardner 1983, 251). When I brought this to Hartshorne’s attention he sent me a handwritten note, dated November 12, 1991.

“Concerning M. Gardner & my knowing too much about God, what he, & so many, miss is that what I claim to know is very little. The mystery is not what extreme abstractions apply to God, but what the divine life concretely is, how God prehends you or me or Hitler, or the feelings of bats, ants, plant cells, atoms. The one ‘to whom all hearts are open’ knows, or loves the concrete concretely. We know nothing in this way. Also [God knows] past cosmic epochs” (Viney 2001, 46).

A fact that many have discovered is that Hartshorne’s neoclassical theology is a standing counter-example to the view that theism, in a scientifically literate world, cannot be intellectually respectable and rationally defensible. This lesson has been lost on the new atheists who still labor under the assumption that God is best understood as a scientific hypothesis, a claim that Hartshorne was at pains to refute. In any event, Hartshorne was no stranger to science. His first book straddled the disciplines of empirical psychology and philosophy (Hartshorne 1934) and he published a well-received book on bird song (Hartshorne 1973).

Hartshorne defied the stereotype of the inflexible elderly person. There was certainly no dogmatism in him. Beginning in the early 1980s he began using inclusive language saying that he agreed with the feminist objection to using exclusively masculine pronouns in referring to God (Hartshorne 1983, xvi-xvii). In April 1987, I took a group of students to Central State University in Edmond, Oklahoma to hear him speak. After the talk a woman remarked on the fact that Hartshorne had used the masculine pronoun for God. I had made a mental note of this as I listened and I assumed that it was a question of the difficulty of breaking old habits. Hartshorne responded that his language was not deliberately chosen and that he had ceased to use such language in his writing. To the amusement of the audience he said, “That’s one of the things I repent of in my writings. It’s one of the things that makes me ashamed of my sex” (Hartshorne 2001, 258).

It was also in the 1980s that Hartshorne began addressing specifically feminist concerns, such as the right of a woman to have an abortion. His article in the Christian Century evoked much controversy in the editorial pages of that magazine and was anthologized a couple of times (Vetter 1982; Rosenbaum 1989).3 In April 1981 he debated Mildred Jefferson on whether selective abortion should be illegal. In a letter of April 12, 1981 he wrote that he found this a “monstrous proposal” (Viney 2001, 9). He also noted that, “Debating is a political activity, not a search for truth.” The debate did not go well for Hartshorne. On May 4, 1981 he wrote:

“I did not win the debate at Dartmouth and I did not debate well. I have never debated formally and don’t like the combative, victory-at-any-cost atmosphere. I did get 47 votes, or my side did, compared to 87, as I recall. My two students didn’t debate very sharply either, whereas one at least of the other two did. But my students had more interest in the truth I am confident. The audience was packed with fanatics, not all students” (Viney 2001, 11).

Hartshorne was more at home in the atmosphere of a philosophy conference where arguments are not assessed by votes and where dialogue is valued.

It was at philosophy conferences that Hartshorne so often earned his reputation for pithiness. At a meeting of the Southern Society of Philosophy and Psychology in Atlanta, Georgia in April 1983 I heard him remark that modesty is the one virtue you cannot boast about. He also related a story about Paul Weiss. Someone asked Weiss if he ever philosophized in his dreams. “No,” he replied, “but sometimes when I philosophize I worry that I’m dreaming.” Exactly a year later, at the University of Nebraska, Hartshorne commented on a paper by James Ross (Ross 1986). Hartshorne prefaced his remarks by saying, “Your paper is well argued and, I think, mostly correct. This is the second time I have heard you deliver such a fine paper. It has been some time since I heard the other paper.” When the laughter subsided, he asked Ross whether he believed that his position entailed that God does not know future free decisions. Ross replied, with as much wit as respect, “With your commendation, I don’t want to risk saying something I may later regret.” Hartshorne sat down and whispered to me, “He is a capable fellow.”

I consider it my good fortune that Hartshorne and my father admired each other. He included in his autobiography a photograph that I took of the two of them standing side by side (Hartshorne 1990, 300). Wayne Viney is a psychologist who specializes in the history of the discipline (Woody and Viney). He and I attended the Atlanta conference and it was there that I introduced him to Hartshorne. It was the only time the two of them met. After the conference we took an early shuttle to the airport so that we could accompany him to his airplane. As we walked through the terminal, Hartshorne commented that he had received a proper escort. I said, “I believe that it is my father and I who have gotten the proper escort.” Hartshorne grinned at my father and said, “He’ll do okay in the world.”

In route to the airport, my father and Hartshorne exchanged anecdotes about Eliseo Vivas, William James, Sigmund Freud, and Gustav Fechner. The two did not see eye to eye on the question of determinism, my father wanting to stress causation more than free will. There was a certain irony in this. Hartshorne claimed that music would always be more influential than the visual arts—specifically, composers would always be more popular than painters. He explained that, at a biological level, a painting in a gallery has far less effect on the senses than the sound of a symphony. I took him to mean that the sound of a symphony is louder to the ear than the reflection of light from a painting is bright to the eyes. My father later told me this bothered him because it seemed too deterministic. Shouldn’t it be possible for anyone to be as great as anyone else? I too had my doubts. Biology is not the only determining factor in fame. There are probably as many reproductions of Da Vinci’s Last Supper in the homes of Americans as there are recordings of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

Two years later, the Library of Living Philosophers volume on Hartshorne was in preparation. Hartshorne was trying to find a psychologist to write an article on his first book, The Philosophy and Psychology of Sensation (1934). In a letter of December 22, 1985 he wrote:

“Is there any chance your father would be interested? The idea is not to praise but to evaluate my work so far as it bears on experimental or empirical facts. [ . . .] You perhaps have some idea of your father’s interests. He might be merely embarrassed by such a suggestion. I admire him and his relation to you. Probably he should not be bothered. I can live with there being no psychologist in the book. But I would like even a severely critical one” (Viney 2001, 27)

My father graciously accepted the invitation and thereby gave notice to an aspect of Hartshorne’s thought that has too often been overlooked (Viney, W. 1991).

Everyone who knew Hartshorne has a favorite anecdote about him. This is mine. In March 1985 I took a group of students to St. Louis, Missouri, to a conference on process theology. A retirement banquet for Leonard Eslick, one of Hartshorne’s former students, was held at the conclusion of the first day. After the meal, Hartshorne was asked to introduce Professor Eslick. He said only, “When I first met Leonard, I knew he was a remarkable young man. As the years passed, he has grown even more remarkable.” Eslick then gave a brilliant, but jargon laden, presentation on causal efficacy in Whitehead’s philosophy (Eslick 1985). The lights were low, we had all been through a busy day of papers, and the meal weighed on our stomachs. I had difficulty staying awake, as did others in the room, but somehow I managed to keep my eyes open. As far as I could tell, Professor Eslick looked up from his podium only once. I followed his line of sight across the room to where the Hartshornes were sitting. Dorothy Hartshorne was asleep, her head nested in her arms which were folded on the table. Charles’s head was beginning to roll backwards, his mouth agape.4 Eslick was undaunted. After the banquet I saw Hartshorne in the coatroom and he asked me what I thought of the talk. I confessed to not being able to follow it very closely. “Yes,” he replied, “it was a bit much to digest after such a heavy meal.”

I believe that Hartshorne would appreciate that anecdote, for he was able to laugh at himself, if the joke was fair, but he did not like to be ridiculed (cf. 1990, 248). He was not pleased with all of the stories that circulated about him. In February 1988, at the University of Texas,5 a philosopher told the assembly a story about Hartshorne’s absentmindedness: Dorothy had counseled her husband to take more interest in the lives of his students. One day Charles saw a student walking across the campus with a baby stroller. When he asked about the student’s baby she replied, “But Professor Hartshorne, this is Emily, your baby, and I am her babysitter.” Hartshorne leaned toward me and said, “That never happened. I would never forget my baby.” Two years after this episode, Hartshorne’s autobiography was published and he alluded to a story of having forgotten that he had a daughter, a legend he called “absurd” (1990, 20).

I can vouch for the following story—even document it with the above photograph— which has a charm all of its own (Viney 2001, 62). In September 1991 I attended a celebration of Hartshorne’s achievements at the Claremont School of Theology. Hartshorne gave a presentation with an overhead projector. At one point he became tangled in the electric cords and Marjorie Suchocki came to his aid. He stood directly between the projector and the screen, casting his shadow onto it, and pointed at the screen as he spoke very seriously about the tables that could only be seen as projected onto his body. This was quite entertaining and somehow appropriate. After all, we had come not only to honor his ideas but also to honor the man, and if this day the man eclipsed the ideas it was only fitting.

Centenarians are often asked for their secret for longevity. Hartshorne claimed no such control over his life. He recognized the wisdom of moderation, healthy diet, and exercise, but he never underestimated the role of luck. He was blessed with good health, even in his twilight years. A letter postmarked December 10, 1992 is full of optimism, commenting on his publication efforts, noting that he had mastered his SCM word processor, and reporting that his physician predicted that he would reach 100 (Viney 2001, 51). Almost three years later I received a handwritten letter, postmarked April 2, 1995, updating me on the publishing of his last book. The letter included a poignant report on his condition: “I can still think, but it takes more time & only my SCM word processor makes it possible, typing no longer possible. Too many mistakes, clumsy fingers” (Viney 2001, 53).

He made a similar statement in October 1997 at the University of Texas at his centenary celebration organized by Robert Kane.6 Those present wondered if he would be well enough to attend the conference. Shortly after the keynote lecture, Charles Richey, Hartshorne’s caretaker, entered the room pushing him in a wheelchair. Hartshorne was wearing a broad-rimmed leather hat and tennis shoes that fastened with Velcro. When Richey wheeled Hartshorne down the center aisle, the audience stood and applauded. Hartshorne addressed us from his wheelchair, holding a microphone. “Old age is almost a disease,” he said, “I have no nameable ailment. I can’t think as fast as I used to. I can’t do anything as fast.” Yet, there he was, fulfilling his physician’s expectations and enjoying the attention of what Hank Steuver called his “fan club” (1997). There is some truth in that description, but our enthusiasm was tempered by the knowledge that this was the last time many of us would see him.

The Austin American Statesman, following the announcement of Charles Richey, reported Hartshorne’s death as October 9, 2000. It was Yom Kippur, the most solemn day on the Jewish calendar, a day of fasting and prayer. The coincidence had meaning for me as I had spent the day in Joplin, Missouri serving as a bass member of a quartet for the synagogue. His death on Yom Kippur was also meaningful because I knew that he was fond of quoting a line from the Jewish prayer:

“Though all things pass, let not Your glory depart from us. Help us to become co-workers with You, and endow our fleeting days with abiding worth” (Stern, 193).

Hartshorne said that the only church he ever financially supported was the Unitarian and his writings show an appreciation of a variety of religious traditions. I asked him (in April 1984) whether he considered himself a Christian. He said that he accepted the great commandments to love God and to love your neighbor as yourself as the essential truth in religion. He added, however, that he did not believe in the divinity of Jesus or that Jesus ought to be worshipped. Nor did he accept the idea of a personal career after death or any sort of afterlife in which rewards and punishments are apportioned. “If you call that Christian,” he concluded, “then maybe I’m a Christian.” Hartshorne’s explanations of his beliefs somehow made my question seem less urgent.

* * *

Over the course of the years that I knew Hartshorne, I received many letters with his return address: 724 Sparks Ave, Austin, Texas. I did not visit that address until after his death. Hartshorne’s daughter (and only child) Dr. Emily Hartshorne Schwartz contacted me with a request to go to Austin to help her prepare her father’s philosophical papers to be shipped to the Center for Process Studies at the Claremont School of Theology. She needed someone with a knowledge of Hartshorne’s work who might be able to identify names of correspondents in his letters and to say whether a particular paper had been published. I loaded my own library of Hartshorne’s books and papers into my car and drove to Austin from Pittsburg. I spent the better part of three and a half days, June 18-21, 2001, sifting through papers and correspondence, the literary remnants of the philosopher’s life.

I prepared a document for the people at Claremont of the unpublished works by Hartshorne that I found.7 There were sixty-seven articles and four forewords to books by other authors (presumably the forewords were never published because the books for which they were written were never published). A few of the items in the list were added from my personal collection.8 In addition, I stumbled across a book-length manuscript that was essentially complete titled Creative Experiencing: A Philosophy of Freedom. Hartshorne was working on the book in the 1980s and I realized in retrospect that, during my first meeting with him in Norman in February 1981, we had discussed a title for the book—he asked me whether “The Structure of Experience” or the “The Structure of Creativity” was better. In the 1980s, other projects and personal concerns took precedence over that book. He contributed to four volumes devoted to his thought during this time and his wife was suffering the effects of Alzheimer’s disease. The last of his books that he saw published, The Zero Fallacy (1997), appeared only thanks to the editorial assistance of his friend Muhammad Valady. Creative Experiencing was put aside or forgotten.

I saw to the publication of some of the articles in two special focus sections of the journal Process Studies (30/2, Fall-Winter 2001 and 40/1, Spring-Summer 2011). Sometime during 2004, John Cobb at the Center for Process Studies contacted me about helping to edit Creative Experiencing, which Jincheol O, a Korean graduate student at Claremont, had rediscovered. (I wondered if the document I prepared for Claremont was somehow lost since both Cobb and O seemed to think this was the first time anyone had seen the manuscript.) Of course, I jumped at the chance to edit Hartshorne’s last book. Soon afterwards I received a panicked telephone call from Emily. She had heard that a graduate student was being considered as editor for her father’s book and she wanted me to intervene and make sure that I, or someone with my expertise in Hartshorne, oversaw the project. I explained that Cobb had invited me onto the project, I had accepted, and I would insure that the project was done professionally. In 2005, during a visit to Claremont, I discussed possible publishers for the book with Cobb; he was extremely supportive and encouraging.

State University of New York Press agreed to publish the book. Approximately half of the chapters were from previously published pieces, so it was necessary to get permission to republish those chapters. Two of the publishers allowed me to republish the articles at no cost, but others were quite costly. The press had no fund for permissions, so Cobb offered to pay half of the permissions bill and I paid the other half. I agreed to edit the work on the condition that the royalties would go to Emily. It seemed the least that I could do for the man who had so profoundly shaped my ideas and my career. The book was published in 2011.

Endnotes

1 I also have Crosby to thank for giving me a thorough introduction to Whitehead and for first opening my mind to the rigors and the possibilities of speculative metaphysics. The paper that Hartshorne presented at the Denver conference was published under the title “Process Themes in Chinese Thought” (1979)

2 In Anselm’s Discovery, Hartshorne mentions Johnson’s “remarkable article” (1965, 139) on Plato and the ontological argument (1963). Johnson studied at Kansas State Teachers College in Pittsburg, Kansas, taking an A.B. in 1957 and an M.A. in 1948. In 1977 the college was renamed as Pittsburg State University, which is where I have been employed since 1984.

3 One of my students, Anita Miller Chancey, wrote an excellent review and critique of Hartshorne’s position on abortion (Chancey 1999).

4 Dorothy Hartshorne was lively and provided the conference with its most charming moment. Before her husband’s talk, the two of them drew some tables illustrating various metaphysical options on the chalkboard. Shortly before the presentation began Dorothy jumped to her feet and corrected one of the tables. As she was returning to her seat she said in a voice audible to the entire room, “It’s a good thing I’m invisible.” When Hartshorne began to speak, Dorothy was in the back of the room and she called out, “Louder!” Her husband obediently spoke more clearly into his microphone. Much later I would learn that it was in 1985 that Dorothy Hartshorne began to show symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. At the conference I did not see any evidence of this. I recall one brief conversation with Dorothy. I asked what she thought of Michelle Bakay’s drawing of Hartshorne on the cover of my book. Her reply, “It makes him look old.” I told Lewis Ford about this. He grinned and said, “Have you seen Beth Neville’s drawing?” I nodded knowingly, for I knew he was referring to the line drawing of Hartshorne in Robert Neville’s book God the Creator (University of Chicago Press, 1968): 267.

5 Papers presented on this occasion and some invited for the volume are in Kane and Phillips (1989). My paper in this volume was not presented at the conference. Robert Kane wrote to me asking that I contribute a paper. The paper I originally wrote was longer than the one that was published. Kane suggested that I cut the paper into two papers. This I did. The other part was published in Process Studies 18/1 (Spring 1989): 30-37.

6 The papers presented on this occasion are published in The Personalist Forum 14/2 (Fall 1998).

7 See pages 24-29 below.

8 During Hartshorne’s visit to Oklahoma in February 1981 he spoke at the First Unitarian Church in Oklahoma City on the subject “Taking Freedom Seriously” and I acquired a copy of that paper. In 1983, Hartshorne gave me a copy of his paper on Troland after he presented it in Atlanta. When Hartshorne was in Edmond Oklahoma, in 1987, he presented his paper titled “God as the Composer-Director, Enjoyer, and, in a Sense, Player of the Cosmic Drama” and, again, I acquired a copy. Finally, In November 1991, Hartshorne sent me a copy of a paper on Thomas Aquinas and three poets. A hand-written sticky note was attached that said, “How do you like this? If too long, take out something, but preserve the intelligibility.” I understood him to be submitting the paper to The Midwest Quarterly, a journal on whose editorial board I sit. This I did, but the editor-in-chief said it was too long and I didn’t want to cut any of it out. As noted in my narrative, I eventually saw to its publication (and to the publication of the Troland paper and the paper from Edmond) in a special issue of Process Studies.

References

Anon. 1981. “Philosopher to Speak.” The Oklahoma Daily, Norman Oklahoma (Friday, February 20): 7.

Borges, Jorge Luis. 1964. “The Witness,” Dreamtigers. Translated by Mildred Boyer and Harold Moreland. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Chancey, Anita Miller. 1999. “Rationality, Contributionism, and the Value of Love: Hartshorne on Abortion.” Process Studies. Vol. 28, nos. 1-2 (Spring-Summer): 85-97.

Cobb, Jr., John B. 1992. “The Philosophy of Charles Hartshorne.” Process Studies. Vol. 21, no. 2 (Summer): 75-84.

Easterbrook, Gregg. 1998a. “A hundred years of thinking about God: a philosopher soon to be rediscovered.” U.S. News and World Report (February 23): 61, 65.

_____. 1998b. Beside Still Waters: Searching for Meaning in an Age of Doubt. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Eslick, Leonard. 1985. “Divine Causality.” The Modern Schoolman. Vol. 62. No. 4: 233-247.

Gardner, Martin. 1983. The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener. New York: Quill.

Hartshorne, Charles. 1934. The Philosophy and Psychology of Sensation. University of Chicago Press.

_____. 1965. Anselm’s Discovery: A Re-Examination of the Ontological Argument for God’s Existence. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court.

_____. 1979. “Process Themes in Chinese Thought.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy, vol. 6: 323-336.

_____. 1962. The Logic of Perfection. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court Press.

_____. 1973. Born to Sing: An Interpretation and World Survey of Bird Song. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

_____. 1983. Insights and Oversights of Great Thinkers: An Evaluation of Western Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press.

_____. 1985. “Process Theology in Historical and Systematic Contexts.” The Modern Schoolman. Vol. 23: 62. No. 4: 221-231.

_____. 1990. The Darkness and the Light: A Philosopher Reflects Upon His Fortunate Career and Those Who Made It Possible. Albany: State University of New York Press.

_____. 1991. “Communication from Charles Hartshorne.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Association. Vol. 65, no. 3 (November): 69-70.

_____. 2001. Audience Discussion of “God as Composer-Director, Enjoyer, and, in a Sense, Player of the Cosmic Drama”. Process Studies. Vol. 30, no. 2 (Fall-Winter): 254-260.

Heschel, Abraham. 1959. Between God and Man. Edited by Fritz Rothschild. New York: Free Press.

Johnson, Prescott. 1963. “The Ontological Argument in Plato.’ The Personalist. Vol. 44: 24-34.

Kane, Robert and Stephen H. Phillips, Editors. Hartshorne, Process Philosophy and Theology. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Rosenbaum, Stuart E., Editor. 1989. The Ethics of Abortion. Buffalo, New York: Prometheus.

Ross, James. 1986. “God, Creator of Kinds and Possibilities: Requiescant universalia ante res.” Rationality, Religious Belief and Moral Commitment: New Essays in Philosophy of Religion. Edited by Robert Audi and William J. Wainwright. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press: 315-335.

Stern, Chaim, Editor. 1975. Gates of Prayer: The New Union Prayerbook. New York: Central Conference of American Rabbis.

Vetter, Herbert F., Editor. 1982. Speak Out Against the New Right. Boston: Beacon Press.

Viney, Donald W., Editor. 2001. Charles Hartshorne’s Letters to a Young Philosopher: 1979-1995. Logos-Sophia: Journal of the Pittsburg State University Philosophical Society. Volume 11 (Fall).

Viney, Wayne. 1991. “Charles Hartshorne’s The Philosophy and Psychology of Sensation.” The Philosophy of Charles Hartshorne. Edited by Lewis Edwin Hahn. The Library of Living Philosophers. Volume XX. La Salle, Illinois: Open Court: 91-112.

Woody, William Douglas and Wayne Viney. 2017. A History of Psychology: Emergence of a Science and Applications. Sixth Edition. New York: Routledge.

Unpublished Manuscripts of Charles Hartshorne

Donald Wayne Viney

I compiled the following list on June 19-21, 2001 at Charles Hartshorne’s home in Austin, Texas as part of my work in helping Emily Hartshorne Schwartz to prepare her father’s philosophical papers for shipment to Claremont, California, in accordance with his final directives. Prior to my arrival—working since January 2001—Dr. Schwartz and others had separated Hartshorne’s personal correspondence from his philosophical and ornithological papers. Part of my task was to review the philosophical papers to ensure that they came from Hartshorne’s pen and to identify published and unpublished material. The list that follows contains only those materials that appeared to me to be complete articles. In a couple of cases, I was not sure whether the item had been published and I made notes accordingly. In the majority of cases manuscripts were not dated. I did not have the luxury of time to read all of the papers, so doubtless there are internal clues that I did not notice that would allow the dating of some of these items. I added item 32 and alternate versions of items 53 and 56 from my personal collection. I have listed the names of the articles in alphabetical order and, in parentheses, the number of pages in each article—unless otherwise noted articles are typed double-spaced. “LLP #” refers to items as listed in the bibliography of the Library of Living Philosophers volume, The Philosophy of Charles Hartshorne, edited by Lewis Hahn (1991). At the end of the list I note the existence of two forewords and two prefaces that do not appear in the LLP listing, but which may have been published. Finally, I attach an addendum concerning the unpublished book length manuscript that Emily and I found in the collection. [Donald Wayne Viney, Pittsburg State University]

1. The Analogy Between Sex Bias and Racism (9)

2. Arthur Murphy on Speculative Philosophy (40)

3. The Best Positivism and the Best Postmodernism (18)

4. C. I. Lewis: Reflections on a Favorite Teacher (10)

5. The Circularity of Arguments For and Against Naive Realism (13)

6. Darwinism and Some Related Topics: A Review Article [of Charles Darwin: A New Life by John Bowlby (NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 1990)] (19)

7. Deconstructing Deconstructionism

8. Determinate Truths about the Indeterminate Future [A reply to articles by P. Fitzgerald and Melvin Schuster in The Review of Metaphysics XXI (1968).](10)

9. Do Philosophers Know They Have Bodies? (15) The abstract of this paper was published in 1974; cf. LLP # 363]

10. Dobzhansky’s Dualism (6)

11. A Divine Kind of Time (13)

12. Ethical Proof: Rational Choice and the Value-Receptacle (19)

13. The Evolution of Free, Self-Creative, Musically Communicating Creatures: Twentieth Century Platonism and the First Complete Positivism (11) [dated Feb. 19, 1995]

14. Evolutionary Theory (17)

15. Experience as Feeling of Feeling

16. Faith, Courage, and Chance (15)

17. My Fifty Years of Progress in Aesthetics (8) [Handwritten note: Is this published in J. of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 51 (Spring 19?? 286- 289)]

18. My Frustrating but Constructive Philosophical Dream (2)

19. [Gilbert] Fulmer’s Refutation of Theism (6)

20. God as Composer-Director and Enjoyer, and in Some Sense Player, of the Cosmic Drama (26)

21. How Edgar Allen Poe, Although a Genius, Was Also an Alcoholic and an Atheist (4) 22. In What Sense Life After Death?

23. Interactionism (without Dualism) (6)

24. Is a ‘Godless World’ an Empirical Idea?

25. Is There a Twentieth Century Metaphysics? (12)

26. [Murray] Kitely on Sense Data (3) [Reply to article in Mind April 1972]

27. A Life as a Work of Art (18)

28. The Logic of Atheism (4)

29. A Philosophical View of the History of Philosophy (21)

30. The Practical Vacuity of Strict Determinism (7)

31. My Profession(s) (16)

32. A Psychologist’s Philosophy Evaluated After Fifty Years: Troland’s Psychical Monism (9)

33. A Rapid Journey into Neoclassical Theism (9) [Dated Sept. 21, 1990. This article seems to have been submitted for publication in an anthology, so it may not belong on this list. It does not, however, appear in the LLP listing, which ends in 1991.]

34. Rational and Empirical Elements in the Knowledge of God (5, single spaced)

35. [Andrew] Reck on Hartshorne: Review of a Review (7)

36. Recollections of Leo Szilard (6) [Sent to Macmillan for a biography—hence, may already be published] 3

37. Reflections on “Observership” (7)

38. Religion in a Scientific Culture (20)

39. Revising the American Dream (20)

40. Science, Art and Religion as Sources of Happiness (19) [1966, Kyoto]

41. Self and Neighbor in Religion and Philosophy (2)

42. Self-Creation and Self-Identity (16)

43. Socially Objective Immortality (12) [1992]

44. Some First Steps in the Metaphysics of Process (15)

45. Some Key Questions in Philosophy

46. Some Metaphysical Principles and Human Values (9)

47. Some Philosophical Convictions (12)

48. Space, Time and the Neglect of Metaphysics (14)

49. Spinoza’s Permanent Contributions (12)

50. The Status of Scholasticism Today (3)

51. The Strange Case of Joseph Conrad (9)

52. Table of Theistic (Atheistic) Options

53. Taking Freedom Seriously (single space) [Lowell Lecture 1983; an earlier version of this paper is dated Feb. 22, 1981, given as a sermon at the First Unitarian Church in Oklahoma City (8)]

54. Theism as Radical Positivism: Minds, Bodies, Yes; Mindless Matter, No. Causality, Yes; Determinism, No (7)

55. The Thinking Animal (8)

56. Thomas Aquinas and Three Poets Who Do Not Agree With Him (21) [There are four complete versions of this paper, ranging in length from 21 to 33 pages—there are two additional versions with pages missing, one with no title. Hartshorne gave the following variations on the title: “Thomas Aquinas, Philosophical Theologian and Some Poets Who Do Not Agree with Him: An Imagined Confrontation”; “Thomas Aquinas, Theologian, and Some Poets Who Do Not Agree with Him: An Imagined Confrontation”; “Thomas Aquinas and Three Poets on God, Freedom, and Immortality: An Imagined Confrontation”]

57. Thomism on Divine Knowledge (14) [Appendix of Chapter X of ?]

58. A Turning Point in the History of Natural Theology (20)

59. Two Philosophical Definitions of God (14)

60. Understanding Freedom and Suffering (?)

61. [Untitled paper on symmetry and direction order in metaphysical concepts; possibly an early version of Chapter 10 of Creative Synthesis and Philosophic Method.] (34)

62. The Ultimacy of Aesthetic Principles (26)

63. The Ultimate Science (9)

64. What is Liberalism? (4)

65. What’s Right—What’s Not Right—in Materialism (13)

66. Why Philosophers Are Needed (11)

67. Why Selective Abortions Should Not Be Made Legal (8)

Forewords and Prefaces

1. Foreword to A. Campbell Garnett’s Naturalism and Religious Faith (ca. 1973)

2. Foreword to Richard Rice’s dissertation, Charles Hartshorne’s Concept of Natural Theology (never published) (6)

3. Preface to the Japanese translation of Whitehead’s Metaphysics (1972) [translation in 1989] see LLP # 475

4. Preface to the Japanese translation of Wisdom as Moderation (1987) [written in 1993] (7)

An Unpublished Book: Creative Experiencing: A Philosophy of Freedom

Hartshorne’s last book, The Zero Fallacy and Other Essays in Neoclassical Philosophy, was edited by Mohammad Valady and published in Hartshorne’s one-hundredth year (1997). The book bears Valady’s editorial mark insofar as he selected the essays—with two exceptions— from among Hartshorne’s published and unpublished writings. Hartshorne approved of Valady’s selection and was deeply grateful for his work as an editor, for editorial work had become difficult or impossible for him in his later years. There was, however, a final philosophical book planned by Hartshorne himself that was never published. The book was to be titled Creative Experiencing: A Philosophy of Freedom. Hartshorne composed a table of contents and a preface. Although Hartshorne was still revising the manuscript when he stopped working on the project, the book, in its essential components, appears to be complete. I include here the table of contents of the book that takes note of previously published chapters—at least the ones of which I am aware. The only overlap between The Zero Fallacy and Creative Experiencing is chapter IV, which appears as chapter 9 in Valady’s edition.

Creative Experiencing: A Philosophy of Freedom by Charles Hartshorne

Preface

Chapter I. Some Formal Criteria of Good Metaphysics

II. My Eclectic Approach to Phenomenology

III. Negative Facts and the Analogical Inference to ‘Other Mind’ (LLP # 261)

IV. Perception and the Concrete Abstractness of Science (LLP # 368)

V. Metaphysical Truth by Systematic Elimination of Absurdities

VI. The Case for Metaphysical Idealism (LLP # 308)

VII. Creativity and the Deductive Logic of Causality (LLP # 354)

VIII. The Meaning of ‘Is Going to Be’ (LLP # 265)

IX. Theism and Dual Transcendence (LLP # 458)

X. The Ontological Argument and the Meaning of Modal Terms

XI. Categories, Transcendentals, and Creative Experiencing (LLP # 441)

XII. The Higher Levels of Creativity: Wieman’s Theory

XIII. Politics and the Metaphysics of Freedom

END